05 Aug The Stoic Ideal of the Good Death

by Annalisa Galgano

As Seneca the Younger waited to die from self-inflicted wounds in 65 CE, he is said to have dictated his last words to friends gathered in his bedchamber. Though this final speech is lost to history, perhaps Seneca recalled the admiring words he once wrote in reference to Canus, another Stoic who chose the time and means of his own death:

“Ecce in media tempestate tranquillitas, ecce animus aeternitate dignus, qui fatum suum in argumentum veri vocat!”

“Behold tranquility in the middle of a storm! Behold a mind worthy of eternity, which summons its own fate to serve as evidence of the truth!”[1]

Essential Question: What did the Stoics believe about virtue, death, and the completed life?

Established in the 3rd century BCE by Zeno of Citium, the philosophy of Stoicism is primarily concerned with cultivating and applying reason to one’s thoughts and actions. By practicing the virtue of reason, Stoics believed that they could achieve a good life, or eudaemonia. Literally translated as “good spirit,” eudaemonia was a term the Stoics used to mean a flourishing life, resulting from living virtuously and in accordance with nature.

Stoicism flourished in the late Roman Republic and the early Empire. Best known for their principled approach to self-governance, many Stoic philosophers became influential political leaders or dissidents of their time. Perhaps most notable among these figures is Marcus Aurelius, who ruled the Roman empire from 161 to 180 AD, and who is widely considered to have embodied the Platonic ideal of the “philosopher king.” In his Meditations, Aurelius privately reflected on his life, death, rulership, and his daily practice of Stoic virtue. Aurelius often exhorts himself to contemplate death, believing that conquering the fear of death enables one to live a virtuous life. He writes: “No one has ever escaped death; man must consider, with that in his mind, how he may live the best possible life in the time that is given to him to live.”[2]

The Stoics not only lived by their virtues of reason, self-control, and acceptance of one’s fate; many Stoics sought to die by these virtues as well.

Zeno, the father and founder of Stoicism, chose to die after he suffered a fall outside the Stoa in Athens. He interpreted this accident as a sign that he had completed his life and no longer aspired to continue living in his old age. As he sprawled on the ground, Zeno reportedly spoke to the heavens: “I come of my own accord, why call me thus?” According to his biographer Diogenes Laertius, Zeno died shortly thereafter of abstentia cibi—refraining from sustenance (what is known today as voluntary stopping eating and drinking, or “VSED”).

A later example comes from Cato the Younger, who chose to take his own life after the defeat of the Pompeian cause to overthrow Julius Caesar’s dictatorship . Believing that Caesar intended to pardon him in order to launder his own reputation, Cato drove his sword into his own abdomen as a final act of defiance. According to the biographer Plutarch, Caesar allegedly lamented, “Cato, I grudge you your death, as you would have grudged me the preservation of your life.”[3]

The deaths of Zeno and Cato were not spontaneous acts of moral courage. Rather, these men had spent years contemplating the “good death.” Death, to the Stoics, was not a random or tragic occurrence. Rather, they viewed death as an essential function of human nature and the culminating event of a life well-lived. In the words of Cicero, “When a man has a preponderance of the things in accordance with nature, it is his proper function to remain alive; when he has or foresees a preponderance of their opposites, it is his proper function to depart from life.”[4] For Cicero,“things in accordance with nature” included reason, community participation, provision for one’s family, cultivation of virtue, and self-determination. In his view, one’s life arrives at its natural end when these elements have irreversibly degenerated.

In the early Roman empire, there was not yet a standard term in Latin to refer to death by one’s own hand.[5] The modern concept of “suicide,” as either a sin or tragedy, did not yet exist. The act of killing oneself was not viewed as inherently moral or immoral, but rather amoral. In certain Roman colonies, one could even apply to the senate for the means to end one’s own life. If the applicant’s reasons were deemed acceptable, he would be provided with a vial of hemlock to self-administer. Euphrates successfully made such an application to the Emperor Hadrian in 118 CE.[6]

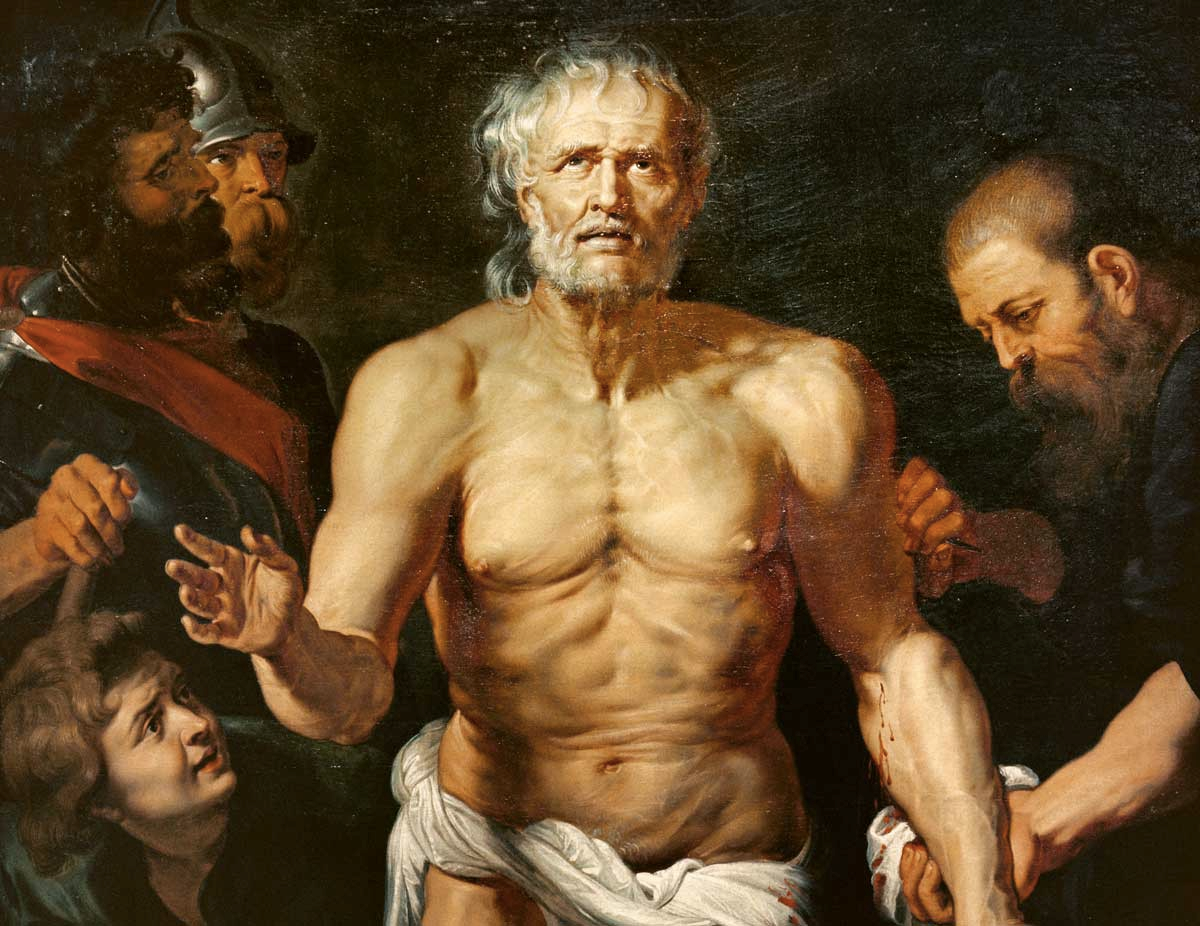

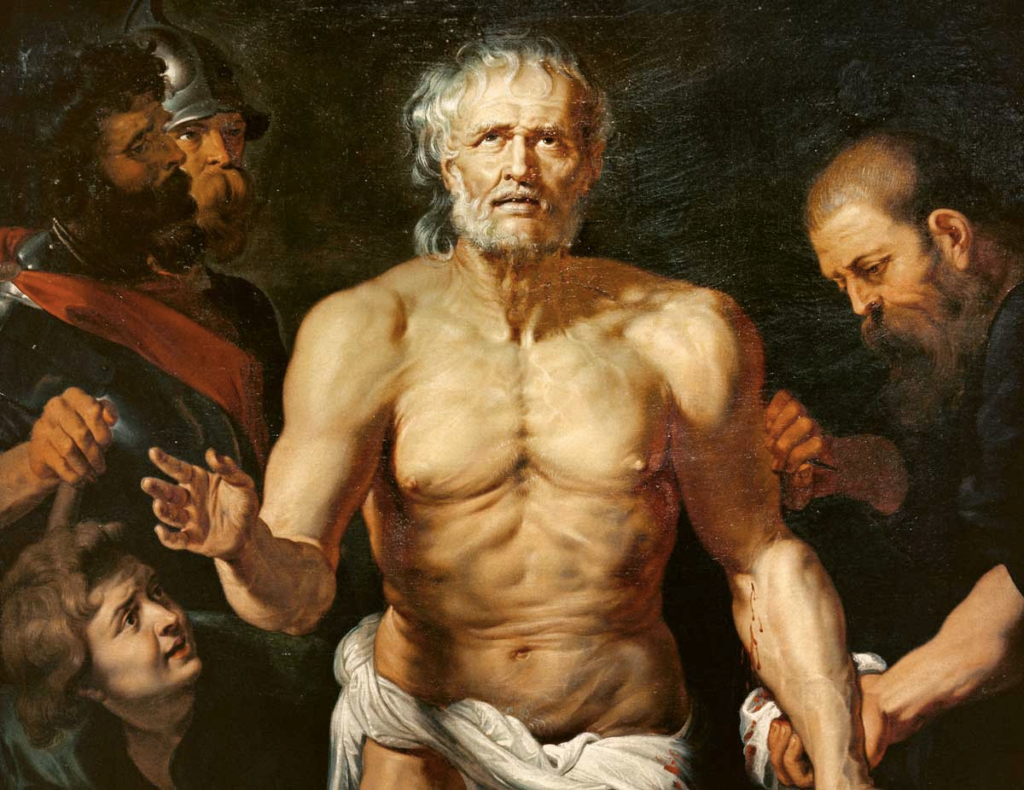

Seneca the younger, prominent in the first century CE, considered death to be the ultimate human freedom, and death by choice an act of courage. He advocated the practice of cotidie mori – or dying each day – so that one would be prepared for the final rehearsal. In his Letters on Ethics to Lucilius, Seneca wrote, “It was the hemlock that made Socrates great. Wrest from Cato his sword, his guarantor of liberty, and you take away the greater part of his glory.”[7] When he was ordered to take his own life for his alleged involvement in a conspiracy against Emperor Nero, Seneca is said to have calmly carried out the order in the company of his friends and family (this scene is represented by Peter Paul Rubens in The Death of Seneca, above).

While they did not judge the action of suicide, Stoics instead drew moral distinctions between acceptable and dishonorable reasons for ending one’s own life. Diogenes Laretius, a 3rd century biographer of Stoic philosophers, defined four honorable motives for ending one’s own life: country (as Cato), friends, pain, and disease (as Zeno and Euphrates).[8] However, the Stoics disapproved of self-killing motivated by “rashness, obstinacy, vanity, love of glory, or ignorance of social duties.”[9] Suicides borne of passion, despair, or dissatisfaction were not considered euthanasia – literally translated as “good deaths.” While the term “euthanasia” has acquired new meaning in the modern context, the Greek and Roman Stoics used the term to distinguish virtuous deaths from unjustifiable murders or suicides.

Epictetus, a contemporary of Seneca, urged forethought and discernment before taking one’s own life. He argued that adversity alone is not sufficient cause, as adversity is inherent to the natural order. However, he encouraged auto-thanasia when one had completed his appointed role. He famously explained this view by using the metaphor of a house on fire: “Do not believe your situation is genuinely bad – no one can make you do that. Is there smoke in the house? If it’s not suffocating, I will stay indoors; if it proves too much, I’ll leave. Always remember – the door is open.”[10] When informed that a friend was actively dying by abstinentia cibi (VSED), Epictetus responded: “If your decision is justified, look, here we are at your side and ready to help you on your way; but if your decision is unreasonable, you ought to change it.”[11]

To the Stoics, euthanasia (good death) was considered the natural capstone to a eudaemonic life. Self-euthanasia, or deciding on one’s own time and manner of death, was regarded as not only morally permissible, but as an inherent human freedom. When reflecting upon this freedom, the Stoics considered the relative virtues of dying versus living and held that death is a choice universally accessible at any moment. When rationally considered, the Stoics saw the choice to die as virtuous and as natural as any other human function. To prepare for the moment of death, one should begin by contemplating their own death each and every day. In the words of Marcus Aurelius: “Think of yourself as dead. You have lived your life. Now take what’s left and live it properly.”[12]

Works Referenced

Aurelius, Marcus. Meditations. Translated by Martin Hammond. London. Penguin Pocket Hardbacks. Penguin Classics. 2014.

Burton, Neel. “ The stoics’ view of suicide.” Psychology Today (April 2022). Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/hide-and-seek/202204/the-stoics-view-suicide

Cicero. “On Ends” 3.60-61, Translated. A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley, The Hellenistic Philosophers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 425.

https://ethicsofsuicide.lib.utah.edu/category/author/cicero/

Cleary, Skye C. “Should I kill myself or have a cup of coffee?” Institute of Art and Ideas News (November 2017). Accessed June 22, 2022. https://iai.tv/articles/should-i-kill-myself-or-have-a-cup-of-coffee-the-stoics-and-existentialists-agree-on-the-answer-auid-924

Dio Cassius. Roman History. Vol VIII: Books 61-70. Translated by Earnest Cary, Herbert B. Foster. Loeb Classical Library 176. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1925.

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/cassius_dio/69*.html

Diogenes Laertius. “Zeno (333-261 B.C.).” Lives of Emminent Philosophers. Book VII, Chapter 1. Edited by R.D. Hicks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1972. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D7%3Achapter%3D1

Epictetus. Discourses, Fragments, Handbook. Book 2. Translated by Robin Hard. United Kingdom: OUP Oxford, 2014.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Discourses_Fragments_Handbook/sNDQAgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Epictetus. Of Human Freedom. Ch 5, 17-18. Translated by Robert Dobbin. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited, 2010.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Of_Human_Freedom/qIZJsZR5X6YC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Ker, James. The Deaths of Seneca. p. 5. Oxford University Press, USA. 2009.

https://books.google.com/books?id=mO1cG_Bt4tgC&dq=death+of+seneca&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Plutarch. “Cato the Younger.” Lives of Imminent Men. Vol. 3. Translated by John Dryden. 1883.. http://classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/cato_you.html

Ruff, Carmine Anthony. “The complexity of Roman suicide.” University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository (1974). https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1956&context=masters-theses

Sadler, Greg. “What does ‘In accordance with nature’ mean?” Stoicism Today. Modern Stoicism (April 2017). Accessed June 30, 2022. https://modernstoicism.com/what-does-in-accordance-with-nature-mean-by-greg-sadler/

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Letters on Ethics: To Lucilius. Book 2. Letter 13. Translated by Margaret Graver and A.A. Long. University of Chicago Press. 2015.

https://books.google.com/books/about/Letters_on_Ethics.html?id=Ob7CCgAAQBAJ

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. On Tranquility of the Mind. 14.10. Accessed June 28, 2022.

http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/sen/sen.tranq.shtml

[1] Seneca, On Tranquility of the Mind. 14.10.

[2] Aurelius, Meditations. VII.46

[3] Plutarch, Cato the Younger.

[4] Cicero. On Ends.

[5] Ruff, C. 1974

[6] Dio Cassius. Roman History. LXIX.8

[7] Seneca, Letters on Ethics: To Lucilius. II.13.14

[8] Diogenes Laretius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. VII.

[9] Ruff, C. 1974

[10] Epictetus. Of Human Freedom. Ch 5. 17-18

[11] Epictetus. Discourses. II.15.6.

[12] Aurelius. Meditations. 7.56.